Every spring and fall—like clockwork—fashion’s elite descend on Paris, London, Milan and New York for something we call “Fashion Week.” Though now a staple in the world of fashion, have you ever wondered how it all began? Where did “Fashion Week” as we know it originate? What is the history behind it?

The modern fashion show has a long and winding history that spans empires, revolutions and key moments in history… and it all began with an Englishman by the name of Worth.

Image via

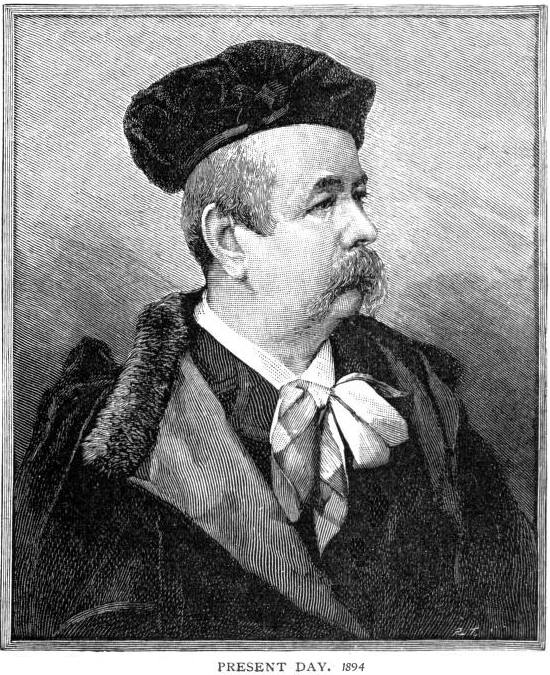

Charles Frederick Worth: The Father of Haute Couture

When someone says the words “haute couture” what is the first thing that pops in your head? Christian Dior? Jean Paul Gaultier? Givenchy? Though these designers have now become synonymous with the art of Haute Couture, a man/genius named Charles Frederick Worth is actually credited as its Founding Father.

Although the focus of this post is not haute couture, it is impossible to address the origin of the fashion show without studying the contributions Worth made to the world of fashion as a whole. His influence on the fashion industry goes beyond the subject of haute couture into the very heart of fashion itself.

An Englishman in Paris

Charles Worth was born in 1825 in Bourne, Lincolnshire, England. At the age of twelve he began an apprenticeship at London’s Swan & Edgar, located just down the street from The National Gallery. His time at Swan & Edgar proved invaluable for two reasons: first and foremost, it taught Worth invaluable lessons about fine textiles and exposed him to the luxurious tastes of the privileged class. Second, the close proximity to The National Gallery allowed him to indulge his artistic passion and study the styles and intricacies of period costumes. In 1845 he left Swan & Edgar for a brief stint at silk merchants Lewis & Allenby. Later that same year he moved to Paris.

Although Worth’s childhood in London proved to be invaluable in honing his skills with textiles and fabrics, it wasn’t until his move to Paris that he took his first steps toward becoming the world’s first true fashion designer (another first credited to Worth!). In 1847, the renowned Gagelin magasin de nouveautés at 83 Rue Richelieu hired Worth as a salesman. The firm specialized in the sale of fabrics, shawls, embroideries and laces to privileged clientele and Worth proved to be an asset to the company. He quickly rose through the ranks and was soon promoted to leading salesman in the shawls and mantles department. This was where he began working with a young demoiselle de magasin named Marie Augustine Vernet.

The First Living Mannequin (aka, The First Model)

To say that Worth was an ambitious man would be an understatement. He was ambitious, intelligent and competitive. As a salesman for Gagelin, Worth experimented with different ways to present goods to potential customers. He would “save the best” for last and entice his customers in a manner that ensured a sale almost every time. He also began using Marie Vernet as a model to showcase the shawls and other items to potential customers.

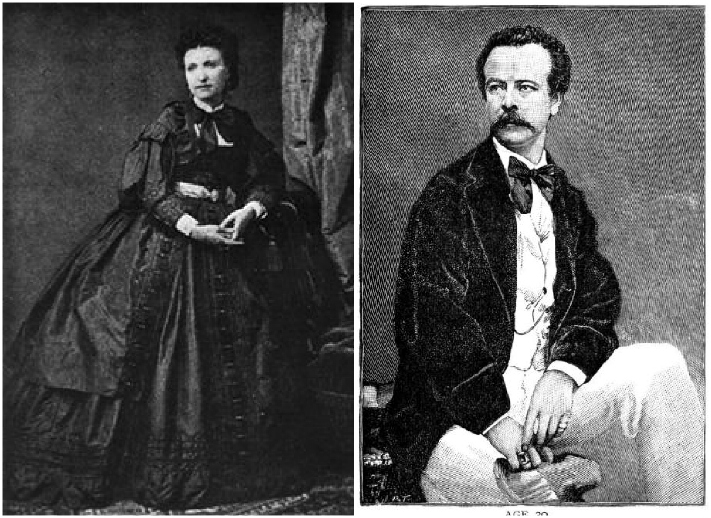

Marie and Charles Worth (via 1 and 2)

It wasn’t long until Worth and Vernet became romantically involved and in 1850 he began designing simple dresses for her that were meant to show off the wares at Gagelin. Marie inspired his creativity, and his designs stood out from the bespoke clothing that was the norm at the time. They were perfectly tailored and elegant in their simplicity. As he had hoped, clients began to notice her dresses which led to increased sales for Gagelin and—more importantly—the first inquiries and orders for Worth’s designs!

As the requests for his work increased, Worth approached his employers and they agreed to establish a small dressmaking shop for him on the premises, with Marie acting as his model. This is believed to be the first time that the sale of textiles and the art of dressmaking were brought together and the first time a man was the dressmaker. Potential clients would come to Worth and, instead of approaching him with their own ideas for a dress, they would pick from a group of existing designs that would then be altered to their particular measurements and requests.

A Rising Star

After their wedding in 1851, Worth continued to design dresses for his beautiful wife and they were seen not only in the shop, but also around town. This led to the couple establishing a now-familiar marketing tactic:

- Worth would design a fabulous new dress.

- The dress was produced for Marie to wear.

- Marie would be seen in the dress both at Gagelin and at events around Paris.

- The orders for said dress would roll in.

It is a format that is still effectively used by designers today (Academy Awards, anyone?) and Worth is credited with being the first to do it.

Around the same time, Gagelin was sold and renamed Opigez & Chazelle. The firm decided to enter the Great Exhibition of 1851 held in London’s Crystal Palace and included several of Worth’s embroidered silk dresses in their exhibit. Worth’s designs helped Opigez & Chazelle win a gold medal in the category of “upper clothing” and helped Worth expand his following. More than six million people came to see the exhibition which was hailed as the first international “trade show” of manufactured products. This type of exposure was unprecedented for a fashion designer and Worth was able to leverage the visibility he received into new clientele.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 (via)

In 1855, another of Worth’s designs was entered by Opigez & Chazelle in the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Known as Worth’s “court train” dress, the design deviated from the standard and had the court train elevated from the shoulders rather than the waist. This innovation, combined with the exquisite embroidery, led to another top prize for the firm.

As Worth’s star continued to climb he realized that he would have to leave Opigez & Chazelle and branch out on his own if he was to achieve the success he dreamed of. Worth had lofty aspirations — he was determined to not only change the way people thought about fashion, but change the art of fashion itself. In order to do that he would need more freedom and a patron of his own.

Worth et Bobergh

In 1858, Worth teamed up with a Swedish former draper’s clerk named Otto Gustaf Bobergh and opened Worth et Bobergh at at 7 Rue de la Paix. In its infancy, the firm was a small one; they employed 20 seamstresses and Marie acted as the main model. Marie would also visit potential clients at their homes and model clothes for them.

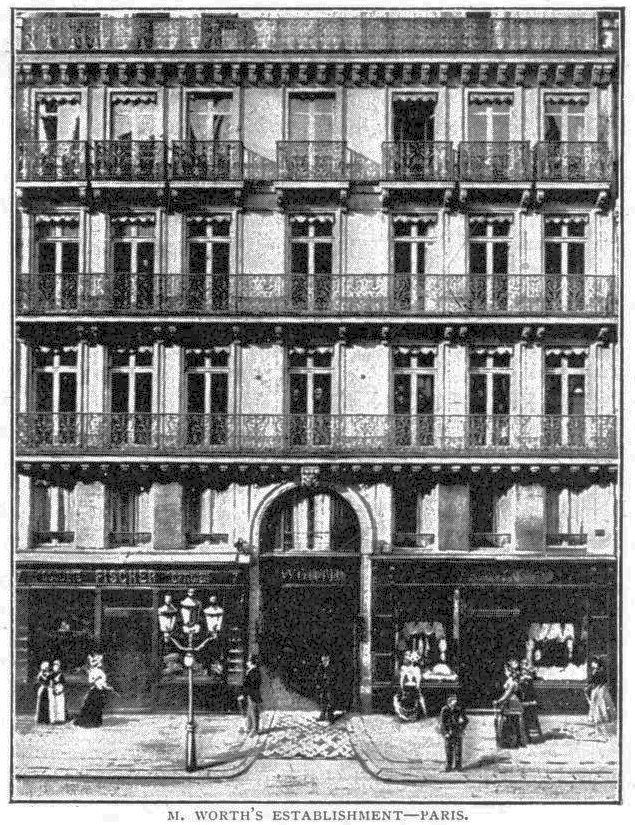

The House of Worth (via)

Worth et Bobergh’s first “official” client was a woman named Valerie Feuillet. Originally a client of Opigez & Chazelle, Madame Feuillet was unsatisfied with the gown they created for her to wear for a ball at the Tuileries Palace. She approached Worth and Bobergh at the eleventh hour and asked them to create a new gown. She was ecstatic when the two men were able to create an enchanting gown of lilac silk covered with spangled lilac tulle, caught up by clusters of lilies of the valley in time for the ball. That evening, the gown caught the attention of the Empress Eugénie who had recently wed Napoléon III. This wasn’t the first time that the Empress had heard of Worth. Opigez & Chazelle had supplied the materials for her trousseau in late 1852 so she was familiar with his work for Gagelin. Nevertheless, she couldn’t believe that the gown had been designed and constructed by a man and—despite her admiration—she did not engage Worth.

Still, Worth’s popularity continued to grow. Now with the complete freedom to do as he wished, Worth was able to move forward with his own ideas and dictate fashion. In addition to one-of-a-kind gowns for the crème de la crème, Worth began designing full seasonal collections his less wealthy clientele could order in their own size. He designed entire wardrobes, including morning, afternoon, and evening dresses, nightgowns, wedding gowns, gowns for masquerade balls, and even costumes worn onstage by the famous actresses and singers of the time. His work was recognizable for its design (he often borrowed details from the period pieces he studied at the Louvre and National Gallery), quality and perfect fit and soon others were attempting to copy his designs. This led to another first — the creation and ownership of a brand name. Worth branded his work and has been credited with being the first to place a label in his designs.

Less than 10 years later, the New York Times would go on describe Worth et Bobergh as a fashion house befitting royalty with “nothing but satin, velvet, gilding, and inlaid wood… enormous mirrors rose from the floor to the ceiling.” It was a fitting description, considering Worth’s most devoted clients ultimately were—in fact—royalty.

The Royal Couturier

Worth knew that it was essential that he find a patron whose influence on fashion was unparalleled. If he could garner the favor of someone with that kind of influence—someone who was a true trendsetter—his success was all but guaranteed. In 1859, he decided to approach Princess Pauline de Metternich, the vivacious wife of the Austrian Ambassador to Paris, Prince Klemens de Metternich. This decision ultimately paved the way for Worth to become the Court dressmaker to the Empress Eugénie.

Princess de Metternich in a Worth Day Dress (via)

The question was — how could Worth first gain Princess Pauline’s favor? The answer proved to be Marie. In order to entice the Princess, Marie went to the Austrian Embassy to speak with the Princess armed with some of her husband’s best sketches. Impressed with the sketches and the sense of artistry she saw in them, the Princess immediately ordered two dresses at 300 francs each and agreed to wear one of Worth’s designs at the next ball at the Tuileries Palace.

For the ball, Worth designed an amazing gown of white tulle spangled with silver and garnished with daisies with pink hearts, placed in bunches of wild grass. The flowers were veiled with white tulle and a wide sash in white stain encircled the waist. The Princess reportedly added her own touch by pinning diamonds all over and, as Worth had hoped, the young Empress did notice the gown and asked the Princess about it.

In Souvenirs de la Princesse Pauline de Metternich, the Princess tells the story in her own words:

“May I ask you, Madam,” the Empress inquired, “who made you that dress, so marvelously elegant and simple?”

“An Englishman, Madam, a star who has arisen in the firmament of fashion,” I replied

“And what is his name?”

“Worth.”

“Well,” said the Empress, “please ask him to come and see me at ten o’clock tomorrow morning.”

“He was made, and I was lost,” said the Princess “for from that moment there were no more dresses at 300 francs each.”

Eugénie had been impressed with Worth’s work when she had seen Madame Feuillet’s gown the prior year, but hadn’t been able to get past the idea of a man as a dressmaker. This time, things were different. Worth came to see her at the Palace the next day and—soon after—she became his benefactor and biggest fan.

By 1864, Worth held the monopoly on Eugénie’s wardrobe. He created all of her clothing, be it court dress, ball gowns, or street clothes. The amount of clothing she required was staggering (imagine multiple gowns a day) and this led to a remarkable amount of work for the firm of Worth et Bobergh. Yet Eugénie was but a single client of many — the firm kept expanding until they ultimately employed over 1,200 seamstresses to keep up with demand. And Worth’s role proved to be more than just a dressmaker — he was known as a true artist. Before an important event his clients would come to the firm for his approval. He was the top stylist of his day, making last minute changes and adjustments until every minute detail was perfect.

1855 Portrait of Empress Eugénie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting by Franz Xavier Winterhalter.

It is rumored that Eugénie is wearing one of Worth’s designs that was presented to her by a friend.

With the Empress as his Patron, Worth became the most sought after and expensive dressmaker in Paris — and perhaps the world. He was known as the Royal Couturier and his label wore the Royal Crest as a symbol of the Empress’ patronage. He enjoyed years of success as the lavish entertainment and spending of the Second Empire continued in France. Although the end of The Franco-Prussian War in 1871 led to the end of Worth et Bobergh’s Imperial Appointment, Worth’s popularity would continue to climb.

In the year following the war, Bobergh left the firm and the House of Worth was officially born. Business was reinvigorated with new clients made wealthy by the Industrial Revolution and the rise of America’s Gilded Age. Few designers could rival the amazing craftsmanship, styles and tailoring found in a Worth original and the House of Worth would continue to enjoy success after his death in 1898 and well into the 1900s.

The First Fashion Show

I know what you are thinking. This whole post is supposed to be related to the History of the Fashion Show, and I am just getting to this now? As I mentioned earlier, I think it’s important to discuss all of Worth’s contributions so that we can put this is the right context. Charles Frederick Worth’s fashion ideology was the precursor of what we know and love TODAY. He was the Father of Haute Couture. He was the First Stylist. He was an Artist. He was the first to use live models. He was the first to design and present seasonal collections. He was the first to hold fashion parades… aka fashion shows.

I mentioned this earlier, but in addition to creating one-of-a-kind designs for his wealthy clientele, Worth also exhibited full collections. He would prepare a full portfolio of designs that were ultimately worn by live models and presented to clients in a fashion parade. The designs the models wore were the equivalent of today’s samples — the client would select the design they wanted, give Worth their color and fabric choices, and their selection would be tailor-made in his workshop. Only a small and select group would be invited to these fashion parades but they were a successful way to increase orders.

Worth is also credited as the first to loan clothing to high profile clients. We know this is common practice today but Worth was ahead of the times. In many ways, the publicity he gained when loaning clothing was greater than when he held a fashion show at the House of Worth. More people would see the design in question meaning the impact was greater. Call it a one-woman fashion show if you will but it was a way of displaying his work.

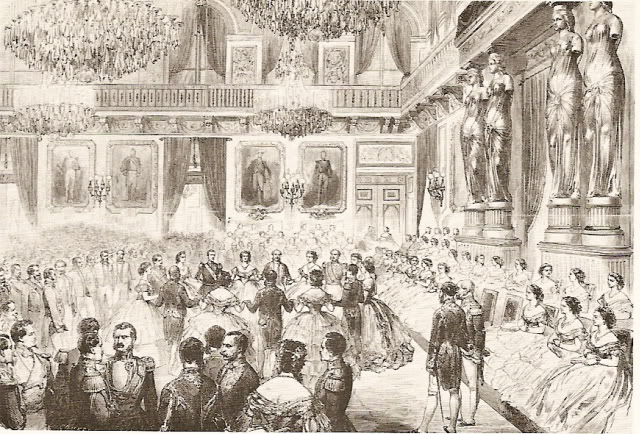

Antique illustration of Grand Ball in Tuileries Palace

Perhaps most significantly, the Second Empire is known for its lavish entertainment offerings. At the height of Eugénie’s reign as Empress, great State Balls and smaller receptions held at the Tuileries Palace, races at Longchamp, military parades, special court appearances, and evenings at the Opera were commonplace. These events would serve the same function as today’s fashion shows–what better way to showcase your designs than to have Paris’ elite serve as your models?

The Trendsetter

There are a million other things that we could write about Worth. He is credited with raining the hem-line of day dresses to clear the ground. He created the princess dress style which has no waistline seam. He helped make the crinoline obsolete by introducing the bustle. He allowed illustration of his designs in magazines. He began selling patterns so that his designs could legally be duplicated in other countries. He was instrumental in founding what would become France’s fashion governing body, La Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture.

His client list included royals like Queen Victoria, Empresses Maria Alexandrovna, Marie Feodorovna and Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia, Queen Alexandra of England, Empress Elisabeth of Austria and Queen Alexandrine of Denmark; celebrities like Sarah Bernhardt, Lillie Langtry and Cora Pearl; and the women of America’s most famous families, including Mrs. J. P. Morgan, The Vanderbilts, The Hewitts and The Astors.

As I type this, the Western Reserve Historical Society in my hometown of Cleveland is hosting an exhibit entitled “Tying the Knot: Cleveland Wedding Fashions, 1830 – 1980)”. The star of the exhibit? The dress Worth designed for Alice Wade’s wedding to Sylvester Thomas Everett in 1879. I was able to see this dress in person and the word “stunning” doesn’t even begin to describe it.

Alice Wade Dress, 1879

Beautiful, right? That beadwork alone is amazing.

Conclusion

I could go on and on about Worth’s contributions to the fashion industry (more than I already have, believe it or not), but instead I have included some additional images of his designs in the slideshow below… but for our purposes today, I say:

Charles Frederick Worth is the Father of the Modern Fashion Show.

Do you agree? Are you interested in learning more about the history of the Fashion Show (Post-Worth, of course!)?

Sound off in the comments below!

-

The Coronation Gown of Empress Elisabeth of Austria

The Coronation Gown of Empress Elisabeth of Austria -

Queen Alexandra of England in gown by House of Worth

Queen Alexandra of England in gown by House of Worth -

Tea Gown by Charles Frederick Worth as seen in Harper's Bazaar, December 1891

Tea Gown by Charles Frederick Worth as seen in Harper's Bazaar, December 1891 -

Empress Elisabeth of Austria in a silk tulle gown spangled with silver stars (makes me think of Emmy Rossum in Phantom of the Opera)

Empress Elisabeth of Austria in a silk tulle gown spangled with silver stars (makes me think of Emmy Rossum in Phantom of the Opera) -

Worth gown worn by Queen Alexandrine of Denmark

Worth gown worn by Queen Alexandrine of Denmark -

-

-

By Charles Frederick Worth c.1888. Designed for Esther Maria (Lily) Lewis Chapin to be worn for presentation at a European court. Sold to a collector for $101,500 at the Doyle Couture Auction of May, 2001

By Charles Frederick Worth c.1888. Designed for Esther Maria (Lily) Lewis Chapin to be worn for presentation at a European court. Sold to a collector for $101,500 at the Doyle Couture Auction of May, 2001 -

House of Worth Evening Dress, c1898

House of Worth Evening Dress, c1898 -

House of Worth Dress, date unknown

House of Worth Dress, date unknown -

Illustration of Worth design in L'Art et la Mode no. 31, 1887

Illustration of Worth design in L'Art et la Mode no. 31, 1887 -

Illustration of Worth design in L'Art et la Mode no. 46, 1885

Illustration of Worth design in L'Art et la Mode no. 46, 1885

Sources/Recommended Reading (warning: you may have to hit the library for most of these):

- The Opulent Era: Fashions of Worth, Doucet and Pingat by Elizabeth Ann Coleman

- A Century of Fashion by Jean-Philippe Worth, 1928

- Worth: Father of Haute Couture by Diana de Marly, 1991

- Souvenirs (1859 – 1871) by Pauline de Metternich

- Land of Desire by William Leach

- Luxury Fashion Branding: Trends, Tactics & Techniques by Uche Okonkwo

- Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850 – 1920 by Patricia A. Cunninghman, 2003

- The Fashion Design Manual by Pamela Stecker

- Designs by Worth and Other Haute Coutures Forum

- The Bourne Archive

- L’Art et la Mode via Les Editions Jalou